The Epiphany of Humility

Well, so that is it. Now we must dismantle the tree,

Putting the decorations back into their cardboard boxes—

Some have got broken—and carrying them up to the attic.

The holly and the mistletoe must be taken down and burnt,

And the children got ready for school. There are enough

Leftovers to do, warmed up, for the rest of the week—

Not that we have much appetite, having drunk such a lot,

Stayed up so late, attempted—quite unsuccessfully—

To love all of our relatives, and in general

Grossly overestimated our powers. Once again

As in previous years we have seen the actual Vision and failed

To do more than entertain it as an agreeable

Possibility, once again we have sent Him away,

Begging though to remain His disobedient servant,

The promising child who cannot keep his word for long.

W.H. Auden, “Christmas Oratorio” ll. 1-15)

I struggle with confidence. Every time I attempt anything public anxiety, self-doubt, and shame overwhelm me. A constant brain refrain is, “I am not smart enough; people won’t read it anyway; they don’t like me; everyone is more qualified than me…” Then, if I am affirmed, I feel on top of the world. Perhaps these experiences are familiar to you as well. The devil of hubris has many guises; the most evident one in my life appears as a roaring lion that seeks to make me cower whenever I begin to attempt anything, then cajoles me into self-aggrandizement if I succeed. The best defence against this beast is practicing redemption through the cultivation of the virtue of humility.

I struggle with confidence. Every time I attempt anything public anxiety, self-doubt, and shame overwhelm me. A constant brain refrain is, “I am not smart enough; people won’t read it anyway; they don’t like me; everyone is more qualified than me…” Then, if I am affirmed, I feel on top of the world. Perhaps these experiences are familiar to you as well. The devil of hubris has many guises; the most evident one in my life appears as a roaring lion that seeks to make me cower whenever I begin to attempt anything, then cajoles me into self-aggrandizement if I succeed. The best defence against this beast is practicing redemption through the cultivation of the virtue of humility.

Humility is often the opposite of what we initially expect it to be. It isn’t the self-denigration that I often find myself wallowing in. In Mere Christianity, C.S. Lewis gives us a good definition of humility:

“Do not imagine that if you meet a really humble man he will be what most people call “humble” nowadays: he will not be a sort of greasy, smarmy person, who is always telling you that, of course, he is nobody. Probably all you will think about him is that he seemed a cheerful, intelligent chap who took a real interest in what you said to him. If you do dislike him it will be because you feel a little envious of anyone who seems to enjoy life so easily. He will not be thinking about humility: he will not be thinking of himself at all.”[1]

Lewis hits it right on the head. Humility is the action of not thinking of my self. Instead it is an absolute belief in who I am and the task I have been called to do: “[to] proclaim the excellencies of him who called you out of darkness into his marvellous light” (1 Peter 2:9).[2] This proclamation is the Epiphany, it is a celebration of my insignificance—I am nothing without Christ in whose very being I discover the valuation of my self. Therefore, my anxiety, self-doubt, and shame are negated by the fact that my self worth is not bound to my worldly success. Instead it is discovered in the joyful proclamation of Christ in and through my actions.

This is both freeing and troublesome. It is freeing because I no longer have to pay attention to my anxiety relating to my abilities to do a certain task. All work becomes meaningful when Christ is proclaimed. For example, a friend cooked me dinner the other night. He thought it was nothing. To me it became an act of infinite worth because in it we remembered Christ. When viewed this way every action and reaction has the ability to become sacramental—everything can be something that proclaims the unity that is found in Christ. It is troublesome because I don’t do this. I forget. I allow my feelings of self worth to dictate my relationship with the other. I forget the love that God has for me is most evident when I love others. This leads me to treat people around me as tool to help glorify myself. When they don’t respond adequately I sink into a slough of despondency. This is because the weight of my glory is upon my shoulders. This is quite a heavy burden to bear, and the longer I carry it the less hospitable I become.

To combat this I need to continually recognize that what I do in public should not be an act of self-glorification. Instead it has the possibility to become the proclamation of God’s “inexpressible gift” (II Corinthians 9:15), the very image of God, “infinity dwindled to infancy,”[3] “the hint half guessed, the gift half understood,”[4] the Incarnation, through which “God/(out of compassion for our ugly/failure to evolve) entrusts,/as guest, as brother,/the Word.”[5] It is through the proclamation of the Incarnation that every act has the possibility of becoming something greater than me, but at the same time, reveals the greatness of my very self because I am participating in the revelation Christ.

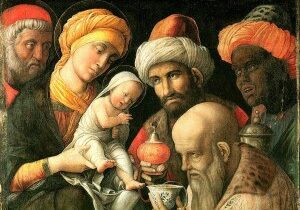

Through the coming of Christ the world is transformed and we, for the time being, can go about shedding our need for validation by practicing redemption in every act we commit. This is the light and glory of the Church that began in the first moments of the Epiphany. By his presence Christ validated the gifts of the Magi who knew him not but still longed to participate in his redemption. Like the Magi, may we too come to God bearing the gift of our riches, our worship, and our deaths, and through these actions proclaim the light of the world until he comes again.

[1] C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (NY: Harper, 2001), 128

[2] This calling is essentially the entrance into grand narrative that I wrote about in my last blog post.

[3] Gerard Manley Hopkins, “The Blessed Virgin compared to the Air we Breathe” ll. 18-19

[4] T.S. Eliot, “Four Quartets: Dry Savages, V” l. 215

[5] Denise Levertov, “On the Mystery of the Incarnation” ll. 8-12

A.A. Grudem

Latest posts by A.A. Grudem (see all)

- How to be Thankful - September 12, 2016

- The Feast of Thanksgiving - August 12, 2016

- The Nicene Creed: “And [we believe] in the Holy Ghost…” - July 7, 2016