Are there really “different ways” of interpreting the Bible?

I want to make an observation about many (not all) of the contemporary controversies surrounding biblical interpretation. I don’t mean historical debates (such as when Paul wrote Galatians or whether John the Baptist was Essene), I mean the application end: what to conclude from the Bible about how Christians should live their lives.

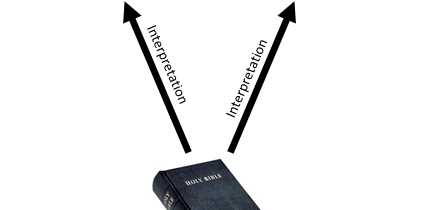

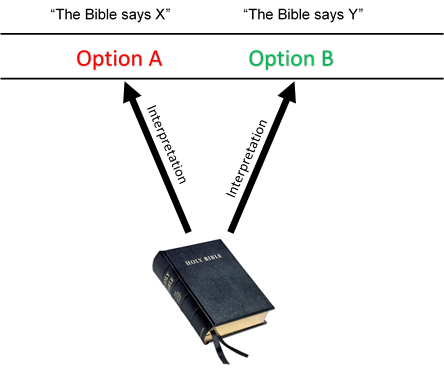

When we say “there are different ways of interpreting the Bible” we often imagine that these alternatives sit alongside one another, like flavours of ice-cream or paths at a fork in the road. We frame the debate in terms of “whether the Bible says X or Y” about a certain topic.

But this way of picturing different interpretations of the Bible doesn’t capture what goes on for the majority of hot topics in today’s Christian world. Consider this list:

- Should women be silent in church?

- Did creation take six literal days?

- Is there such a place as hell?

- Is Jesus really God?

- Is church leadership only for men?

- Is homosexual marriage sinful?

- Should women wear head coverings in church?

- Should Christians care for the environment?

Every item on this list has something in common. They are not really competing interpretations of the Bible, at least, not directly. Of course, those who argue against the above points would say that they get their resources from other parts of Scripture that don’t directly mention these topics. But before they can do that, they first have to show that the Bible verses which do mention the topics are not to be taken ‘literally’. The initial debate is about whether the Bible does or doesn’t speak directly into that topic.

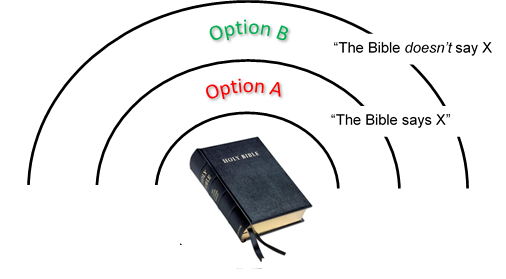

Therefore, the question is really about how closely we can stick to the literal sense of Scripture in our ethical considerations. We should picture the alternatives more like this:

The fundamentalist has an inward movement: sticking to the literal, obvious meaning of Scripture, with as little distance as possible between it and ourselves. But I don’t know anyone who takes the Bible ‘literally’ on all the above points with no cultural distance. I certainly don’t.

Contrastingly, modern exegetical tools of historical criticism push us outwards, making less and less of the Bible’s content directly applicable. We may know more and more about what a Bible text meant in its own context, but we are less and less able to apply it to our lives. Two expert exegetes may agree completely on what a Bible verse meant in its original context, and yet disagree entirely on how to apply it today. It seems that the professional discipline of exegesis does not equip you to make those kinds of judgments.

But if the Bible doesn’t directly forbid/command something, where do we turn for guidance? For Protestantism, or at least for anyone who holds to the sola scriptura principle, there is nowhere else to turn but our own reasoning processes.[1] And the gravitational pull of the surrounding culture’s common-sense assumptions is strong. We almost always end up believing by default what the secular world around us believes. This is usually justified by one or two general biblical principles which secular culture happens to agree with, such as freedom, equality, non-judgmentalism, etc.

So historical criticism, i.e. pure exegesis, has as many problems to solve as fundamentalism. The one-dimensional “conservative-liberal” alternatives lack the depth of perspective to see the above issues for what they are, because both sides remain firmly rooted in the perspective and assumptions of the prevailing culture.

I want to suggest the following ways forward:

- We must listen to each other’s interpretations across the breadth of the global Church. A good theology is dependent on a solid ecclesiology, which sees the church as united in the search for the will of God, and rejects the individualism which assumes I can find all the answers for myself without anyone’s help or correction.

- As well as exegesis, which focuses on what makes a text’s context different from our own, we need another discipline which rebuilds the connections, showing us what principles remain the same across all cultures and ages. This is what theology strives to do, and why theology must come both before and after good exegesis.[2]

- The Christian tradition must be given some real authoritative weight, not just casually listened to for interesting insights. Just because an interpretation of Scripture makes sense in my own head doesn’t mean I can ignore a traditional interpretation which conflicts sharply with mine. This is because the tradition is simply many generations of Bible readers carrying different sets of cultural assumptions. Anyone paying serious attention to the tradition thus has a perspectival advantage over an individual or group which operates in a single generation or culture.

Biblical exegesis must be seen as what it is: an essential piece of a bigger theological organism, each part of which needs the other in order to operate.

[1] Wolfhart Pannenberg makes this point excellently in “The Crisis of the Scripture Principle,” in Basic Questions in Theology; Collected Essays. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1963).

[2] Gerhard Ebeling makes the point that biblical theology cannot survive without dogmatic theology, because all biblical theology begins with the dogmatic underpinning of the authority of the Bible. See “The Meaning of ‘Biblical Theology,’” The Journal of Theological Studies VI, no. 2 (1955): 210–25.

Further Reading

On this blog:

- Rachel has written about the future of theological interpretation.

- Ryan has written about “when we don’t like what’s in the Bible.”

- I have written about the “Clarity of Scripture” in relation to debates on homosexuality in Evangelicalism.

Books:

Grant, Robert M, and David Tracy. A Short History of the Interpretation of the Bible. London: SCM Press, 1984.

Barney

Latest posts by Barney (see all)

- The Nicene Creed: “One Church” - July 14, 2016

- The Nicene Creed: “…for us and for our salvation…” - June 24, 2016

- Pacifism and Politics: The Tank and the Letter - May 3, 2016