Physician-Assisted Death: A Few Thoughts About the Canadian Situation

In this blog post I am going to make a variety of observations about physician-assisted death (PAD), physician-assisted suicide (PAS), and euthanasia, in no particular order. Note that each observation will be necessarily compact and incomplete; these are not to be taken as definite statements but pieces of a puzzle to be mulled over as I (we, I hope) reflect on Canada’s situation.

For those of you not familiar with what is happening in Canada, here is a (very) brief overview: In early 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the prohibition of physician-assisted death (PAD) was unconstitutional for a competent adult person who “clearly consents to the termination of life” and has a “grievous and irremediable (including an illness, disease, or disability) condition that causes enduring suffering that is intolerable to the individual in the circumstances of his or her condition.” Legislation following the SCC ruling is yet to be passed.

- Definitions

Definitions are crucial. To re-define something is often to change what it is. The Supreme Court has chosen to use the term PAD (physician-assisted death) instead of PAS or euthanasia. They do refer to PAS and euthanasia in the ruling, but only in reference to past court cases that have used that terminology. I note two problems with this change of wording: it is parasitic on language used for palliative care and it can come at the cost of clarity. The term PAD itself does not have a set definition the way euthanasia and PAS do. For example, there’s nothing in the term PAD that tells me whether it allows for a direct injection of a lethal substance by a physician (i.e., euthanasia). Euphemisms help remove stigma from the act, but this comes at the cost of clarity. Polls in 2013 and 2015 in Quebec, where they have tabled legislation for “medical aid in dying,” showed confusion about what this meant.[1] A 2015 poll of health-care professionals in Quebec showed that only 40% realized that medical aid in dying meant administering lethal substances at a patient’s request. In the 2013 poll, only 30% of respondents answered correctly that medical aid in dying, as proposed by the bill, involved “a doctor giving a patient a lethal injection.” An alarming 27% thought that it just meant providing medical care to people with terminal illness.[2] This brings me to my second point. Language about physician assisted death, or medical aid in dying, is parasitic on other types of medical care that we (rightly) value, namely hospice care for palliative patients. Hospice palliative care sees itself as physician-assisted death while being strongly against hastening or causing death. Re-defining is not always a bad thing, but it is powerful. In this case, changing from the word suicide—a word denoting a specific action or set of actions—to death, a universal experience, has strong universalizing tendencies. Euphemisms help remove stigma from the act, partly because they help to morally redefine the act. Calling suicide “death” is a lot like calling murder “death.” The end state is the same, but surely we don’t want to pretend they are synonymous.

- Suffering

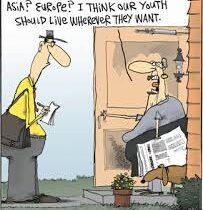

While we’re on the topic of definitions, of note is the fact that the Supreme Court has not defined the terms grievous, irremediable, or suffering. Is suffering a purely subjective experience or are there objective criteria? This question becomes even more important when we consider someone who has a living will or a surrogate decision-maker: who decides when a person reaches an intolerable level of suffering? Who is qualified to determine that the level is intolerable? Must the suffering be physical pain, or does mental anguish suffice? This question has become important in the Netherlands, where a growing number of people who have many years of life left (from a physical/medical standpoint) are choosing assisted death for things like loneliness. It seems to me deeply cruel to shut away our elders in nursing homes and other living arrangements, cut off from relationships and ties with wider society, and then have the gall to pretend that they are exercising free choice in killing themselves. The question of suffering and mental anguish also raises important questions for the field of psychiatry, which “is challenged to balance patient autonomy with benevolent intervention.”[3] What makes suffering a rational basis for suicide and not a condition to be treated?

- Illness, Disability, and Vulnerable persons

Many concerns have been raised from the disability community regarding the SCC ruling. Dr. Dick Sobsey (rightly, I think) states that “Our belief that we should prevent most suicides while encouraging and assisting suicide for some individuals [i.e., those with illness and disability] represents our own biased views of illness and disability.” He goes on to ask why is it that we post a suicide watch on a prisoner who has committed terrible crimes against children, who will certainly be abused by his fellow prisoners, etc. but allow for and even encourage suicide in the case of those with illness and disability. This attitude, he suggests, betrays our normative view about what it means to be a person. Furthermore, in the language used by this ruling, and because this ruling is grounded in the autonomous rights of individuals, I cannot help but note that dignity is being equated with autonomy. Although this sounds good to those of us who are abled, it has deleterious consequences for how we think about people with disabilities. Is it inherently a state of indignity for my husband to feed me, clothe me, change my diapers? These are some of the most loving actions a parent does for a child. Is there no other relationship in which these actions are dignifying? Jean Vanier writes, “This is why we have a special obligation to ensure that the care available to each of us throughout our lives, but especially in our final stages of life, affirms both our dignity and humanity. Otherwise, we diminish our range of experience to include only our independence. We diminish the love we can share, and the vulnerability we can show to one another.”[4]

There are so many other things to be said on this topic, not least the issue of access to palliative care, whether PAD should be considered a medical treatment, the relationship between autonomy and the common good, the reliance of autonomy on social structures and institutions that safeguard it, and interesting developments in the Netherlands and the US. But this, I think, is a good place to begin.

[1] Harvey Chochinov, “Physician-Assisted Death in Canada,” JAMA 315 (2016): 253-4.

[2] http://www.lifecanada.org/images/National%20Polls/Life_Canada_-_Results.pdf

[3] Olivia Duffy, “The Supreme Court of Canada Ruling on Physician-Assisted Death: Implications for Psychiatry in Canada,” CanJPsychiatry (2015):591–596.

[4] http://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/in-assisted-dying-remember-this-we-all-are-fragile/article28964162/ I encourage all of you (and especially my Canadian readers) to check out the Vulnerable Persons Standard: http://www.vps-npv.ca/eng

Robyn

Latest posts by Robyn (see all)

- I’m A Man But I Can Change? Human Nature and Human Enhancement - December 12, 2016

- The Nicene Creed: “…to judge the quick and the dead…” - July 4, 2016

- Can Hermeneutics be Ethical? Ricoeur and the War - June 7, 2016