Netflix and Chill?

When I was surfing the internet, as one does these days, I came across an article that I read and promptly forgot where I read it.[1] But the main content of the article, and one line in particular have stood with me. The author was waxing eloquent about his nostalgia for the emo music of the previous decade when it “was cool to care.” He contrasts this with current popular music, which eschews emotion in favour of a studied detachment. The article stuck with me for two reasons. First, although emo music was never something I got into in my younger days, I listen to a fair amount now because my husband loves it. The whining despair and hopeless situations of these poor musicians cannot help but put a smile on his face and an extra spring in his step. The second reason it stuck with me is that the author’s descriptions of current pop music put me in mind of the tormented souls of men and women who are described by Dante (in his Inferno) as unwanted by either Heaven of Hell because they had “kept themselves apart,” because their passions were so lukewarm that they had failed to live life.

Kathleen Norris, in her book Acedia and Me, makes reference to these same tormented souls who live neither in Hell nor Heaven. Their predicament, she writes, is an indication of the vice of acedia.

Acedia is one of the eight bad thoughts described by the monastic desert Fathers. As Norris explains, these eight bad thoughts would eventually be distilled down to the seven deadly sins. When this happened, acedia was distilled down to sloth but this, Norris holds, was a mistake because sloth is almost always regarded as a physical failing. Acedia is not limited to the physical but occupies a liminal status between the physical and the spiritual. It affects both the body and the mind; it is a spiritual vice and a bodily affliction.

The descriptions of acedia that Norris gives throughout her book show the wide range of this vice. Acedia, she writes, “contains within itself so many concepts: weariness, despair, ennui, boredom, restlessness, impasse, futility.”[2] Acedia often starts as mere laziness but develops into full-fledged despondency. “The desire to avoid hardship becomes the dread of taking any action at all, and particularly of beginning to do any good thing. Soon we despair, not only of our own efforts but also of the mercy of God. As we grow ever more sluggish, negligent, and careless, we come to a “dull coldness that freezes the heart””[3] It is this strange combination of restlessness and listlessness, sloth and discontent, Norris explains, that fuels our need for a constant feed of new things, new experiences, and new entertainment. Sometimes acedia manifests itself not as sloth, but as hyperproductivity as we seek to throw off the feelings of despair by grasping for control by our own means.[4] With this added element, it may seem that acedia is just a word with no meaning, with too many definitions applied arbitrarily. But at its core, Norris explains, acedia is the loss of joy in life, in the gifts of God, and worse than that loss, it is also the complete lack of care. Not only do we cease to take joy in the gift of life, but also we fail to feel guilty about it.

If Norris’s descriptions of acedia seem abstract and far from my own reality, it is the descriptions of how it manifests in her life that really hit home. She describes how sometimes, when she is too lazy or full of despair to write, she tells herself that what she needs is a break. So she picks up a trashy novel. Two days later, she has devoured four or five such novels, failing in that time to shower or feed herself properly, opting for microwave popcorn as she lies listlessly on the rumpled covers of her unmade bed. Replace trashy novels with “Netflix” and how many of us can say we have not been there? Acedia removes even our desire to care about ourselves, about our bodies. We give in so much to despair and indolence that we fail even to engage in the ritual of bathing and eating, rituals that are at the heart of the Christian life.

How to we break the cycle of acedia? This is an important question for me. Right now I am in a sort of honeymoon period; I am at the beginning of new things: a new city, a new program, and a new living situation. (Same husband, though!) All of these things seem exciting and wonderful but I know that before too long, acedia will pop its ugly head and I will find no joy in any of these things. I will become indolent and slothful, and worst of all, I will tell myself that it does not matter, that I should not have to care about being a good scholar, a good wife, a good housemate, a good god-mother. I will be in danger of one of two extremes: either finding myself wrapped in self-importance, as if my academic successes are necessary for the continuation of the world and are solely of my own doing, or else finding myself rumpled and stinky, sprawled out on the bed letting endless episodes of Netflix wash over me, all under the self-deceptive guise of “taking care of myself.”

The answer to the problem of acedia, Norris explains, is as complex as the vice itself and requires spiritual discernment. Norris finds help and comfort in the writings of the monastic Abbas and Ammas, who knew so well the temptations and vices of the human soul and what to do about them. Sometimes their advice to a monk suffering from acedia was the stay in his or her cell, praying as much as possible, and staying there even if prayer was impossible. Other times, their advice was the opposite, telling the monk to find encouragement in the company of others. Much of their advice, Norris notes, for avoiding bad thoughts is similar to one of today’s popular treatment for anxiety and depression, Cognitive Behavioral Treatment.[5] For Norris, dispelling acedia is sometimes it is as simple as re-entering daily life, as simple as taking care of herself. Thomas Aquinas advised those suffering from acedia to have a bath, drink some wine, and get a good sleep. In a world that values hyperproductivity and 24/7 activity, Norris finds the rituals of bathing, doing dishes, sitting and reading, resting, and eating to be a prayer and an act of faith. These daily activities are acts of humility, reminding us that our work is never as important as we think it is, and that it is God, not us, who holds up the world.

When I began my master’s thesis, I was given a prayer by another contributor of this blog, Rachel. The prayer opened with the lines: “Dear Lord, Thank you for this day, a day in my life.” Just one day, a day that will be much like the last and much like the next. Norris encourages us to see this day not as a tiresome repetition, not as part of the extended slog from birth to death, but as a gift from God. She reminds us that when Jesus taught his disciples how to pray, he did not teach them to ask for things for tomorrow and the next day and a year from now. He taught them (he teaches us!) to pray for our daily bread. Each day is one more day in which I can be faithful, one more day in which I can work for his glory, one more day to experience the richness and pain and struggle and joy of this daily life.

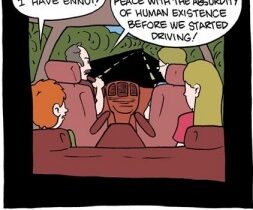

[1] Complete apologies to the poor forgotten author of this article. Also, a special shout-out to Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal (www.smbc-comics.com) for the excellent comic about ennui.

[2] Kathleen Norris, Acedia and me (New York, NY: Riverhead Books), 231.

[3] Norris, 151.

[4] Norris, 160.

[5] Norris is very clear in this, though, that she does not believe acedia and depression to be the same thing, nor is she against anti-depressants and therapy for the treatment of mental illness.

Robyn

Latest posts by Robyn (see all)

- I’m A Man But I Can Change? Human Nature and Human Enhancement - December 12, 2016

- The Nicene Creed: “…to judge the quick and the dead…” - July 4, 2016

- Can Hermeneutics be Ethical? Ricoeur and the War - June 7, 2016