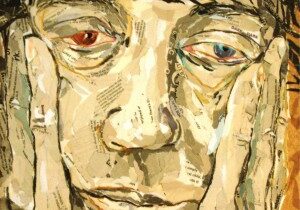

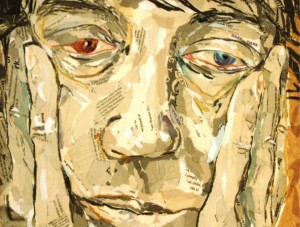

Compassion Fatigue

Compassion Fatigue

The hospital at night is another planet. Gravity sucks 40% stronger than in my cozy little apartment on earth. When the pager vibrates, I jerk into a bleary but adrenalized wakefulness. I lie blinking at the squared-off ceiling of the on-call room, the same kind we shot pencils into at school. I leverage the weight of my sleepy body and wriggle to reach the pager on the floor. The room is small enough, anyway. I wonder why I have signed up for such a job.

When I do call, a nurse tells me that a 42-year-old man has been severely beaten and they cannot find any family for him. Can I come look through the file?

I set my alarm for five minutes and drift back into sleep.

Eventually I schlep down to the emergency department and into the trauma bay. Usually this room is a chaotic snaggle of colors: techs in green, respiratory therapists in black, phlebotomists in maroon, nurses in baby blue, doctors in their white coats. But tonight the room has almost entirely cleared. A portable X-ray machine looms at the sidelines.

A young nurse with a ponytail looks up from her computer in the corner.

“Chaplain?”

“Yeah.”

She turns to look at her patient, the tube in his mouth, the beeping monitor with its undulating numbers.

“We heard he has a daughter, but we can’t find her. He won’t make it through the night.”

“All right. I’m on it.” I say, trying not to look at the patient’s bruised and fractured face, the naked body no one has covered.

I find a desk at the nurse’s station and rifle through old medical notes. I look him up on the white pages, Facebook, Google, keep searching for this daughter I do not want to find.

On nights like this I wonder why I have chosen this job. I’m an introvert. I’m sensitive. I need plenty of sleep. I have a master’s degree and make less than $30,000 a year. I watch hustle and flow of the ED—a psych patient with matted hair staggers leans on her sitter’s arm, a cop types away on his Toughbook—and try to remember why I made this commitment.

* * *

In college I volunteered for a psychology study on marriages that had lost their way.

I sat in a gray cubicle and listened to interviews through a set of padded black headphones. I coded each line of dialogue, assigning a numerical score according to how negative or positive it sounded to me.

Most of the couples they counseled had been married ten or twenty years. One couple argued at length over who got to sleep on the thicker pillow. Another woman complained about she and her husband’s disparate sex drives. When he couldn’t detect much warmth between the husband and wife, the counselor often led them to talk about their earliest memories of each other: how they met, what they first noticed about the other, how they fell in love.

There was a reason you made this decision, he seemed to say.

* * *

As 2 a.m. yawns into 3 a.m. I hear a gurgled scream and a scuffle of shoes on the tile floor. I step out from behind the counter and see a security guard holding down a patient who’s ripped out his IV and is bleeding out of the crook of his elbow.

“Geez, what’s he on?” I ask the nurse, settling back into the rolling chair.

A secretary named Britney, who’s wearing a fresh blonde weave and fake eyelashes, says, “Oh, I think he did bath salts.”

“Bath salts?” says the nurse at the next computer. “I thought they stopped those in the 90s.”

“I guess he didn’t get the memo.”

“I didn’t even know that was a drug.” I say.

“Shoo, girl,” Britney exhales. “That stuff will melt your brain so fast.”

A visitor walks out of his wife’s room. He wears khaki pants and a polo, as if he planned to go golfing before his wife took ill. “What’s going on?” He asks.

The three of us look up.

“Just Saturday night at the hospital,” says the nurse, shrugging.

. When I finally contact the daughter, I don’t tell her that her father’s not going to make it. I don’t tell her that the Cat Scan revealed so much brain damage that the staff has transitioned to comfort care. I don’t tell her that he’s bleeding out of places one should never bleed. I just tell her she needs to come to the hospital. As I wait for her to arrive, all I want is to be excused, dismissed, passed over for this task.

* * *

My own pre-marital counselor talked about the same phenomenon, the initial mark of love you can always return to. She calls it the “love tattoo.”

“Ask people to talk about how they fell in love, their first memories of each other, and their affect will completely transform. They’ll laugh, blush,” she tilts her head from side to side in a Pollyanna-ish imitation of new love. “You won’t always feel that way. In five or ten years, you might feel bored or frustrated. But you can always come back to that love tattoo.”

* * *

When the woman arrives and hears the news of her father, she slides onto the floor and spits profanities at the doctor and me. I sit with her in a dim, empty waiting area while she seethes and ignores me. She pulls out a flip phone and calls someone.

“My daddy died!” She hollers at them through a wash of tears. “I just saw that brother yesterday.” She stops her flip-flops against the tile. “I’m sick, I’m sick, I’m sick. I’m sick, brother, I’m sick.”

* * *

Maybe I have lost my way in ministry, cannot find my love tattoo. Is it too early in my ministry to use the word ‘burnout’? How many of these deaths must I witness before I can say ‘compassion fatigue’?

Kathleen Norris calls this phenomenon “acedia.” She says, “At its Greek root, the word acedia means the absence of care. The person afflicted by acedia refuses to care or is incapable of doing so.” She goes on to say that we lose our ability to care because caring hurts; it means to lament on behalf of someone else.

On nights like these, when I feel acedia toward my vocation, I try to remember what marriage counselors say about commitment. I try to search for my vocational love tattoo, the first time I marveled at a patient’s story or the first time a patient told me I made them feel better, more peaceful. I look not only for the first pangs of my love for ministry, but the moment I first knew God loved me.

Caroline

Latest posts by Caroline (see all)

- Planting: a millennial’s guide to motherhood. - October 10, 2016

- A Net for Catching Days - December 1, 2015

- The Miracle of Flight - September 21, 2015