The Incoherence of Evil

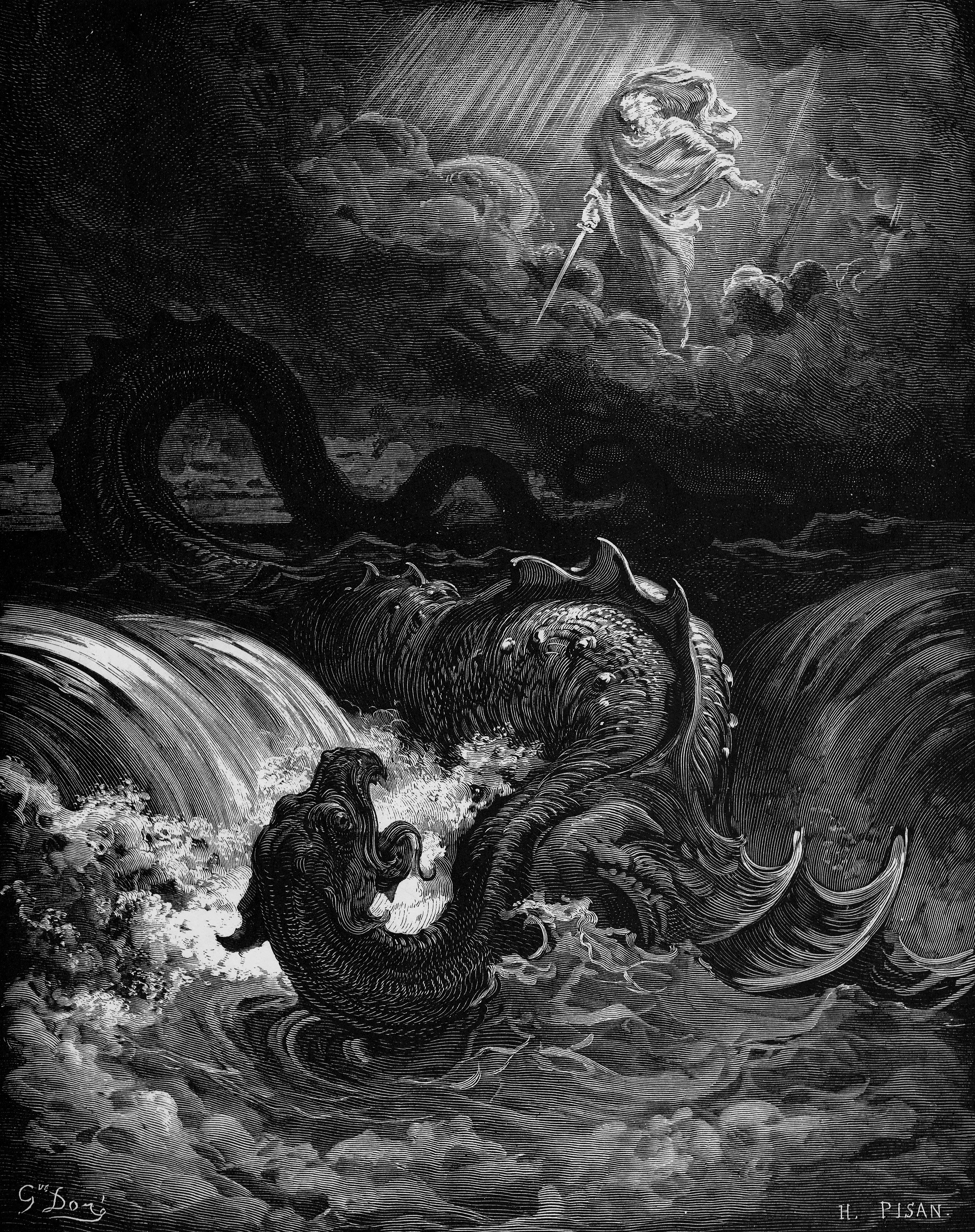

“The Destruction of Leviathan” by Gustave Doré

The world we live in is filled with wickedness and suffering. From the eons of death in our evolutionary history, to acts of war and violence in the world today, suffering is a fact of life. This has forever raised questions for humanity about the God or gods of this world. This often leads to attempts to “get God off the hook,” formally known as theodicies. Everything from pedagogy (God lets us suffer to teach us) to punishment (we suffer because of our sin), and a whole range besides.

Strangely, for all the ink spilled on the part of Christians to try and explain the problem of evil, Scripture seems empty of theodicy. That is not to say that the writers of Scripture are unaware of the issue, but the Bible never gives overarching reasons for why suffering itself happens. Indeed, the Bible’s main text of “theodicy,” Job, seems to speak against theodicy.[1] It is Job’s friends, condemned by God, who try and give a reason for Job’s suffering. Job himself speaks to God, and God answers… but not with a reason. Instead, we are assured of God’s providential care and our own inability to understand.

It is here, however, that I think one of the classic theodicies has something to say, if read rightly. Coming from a Platonic worldview, St. Augustine, among others, appealed to the fact that evil was no-thing. That is not to say that evil has no effect, but that it has no essential reality created by God. Instead, evil is always some sort of corruption of the good. Used to try and understand why evil exists, or to explain why someone is suffering, this response quite obviously falls short, but it does say something very profound about the experience of evil, and something which aligns quite well with Scripture’s lack of theodicy–evil is incoherent.

St. Maximus the Confessor, on whom I am writing my thesis, speaks of evil as no-thing in a way similar to Augustine, and his specific metaphysics helps to bring out this feature of the classical theodicy. According to Maximus, the fundamental ordering of the universe is according to various logoi. The Greek word here is quite multivalent, signifying everything from words to reasons, having also a long philosophical tradition behind it, and much of this is taken up in Maximus’s notion. The logoi are something like Platonic forms, being the divine ideals according to which the world runs, but they are also the specific will and purpose of God for each and every thing, including their creation, current existence, and future destiny.

Reality, however, does not always exist in a way commensurate with the logoi, and it is when beings exist in ways contrary to their logoi that evil, discord, hatred, and suffering enters the picture. Precisely because reason and meaning in the universe are found in the logoi, however, this means that evil presents itself as utterly senseless, “evil is groundless, because it was not created for some purpose, it therefore lacks natural definition. For it has no logos to interpret what it is, and hence of necessity it is not in accordance with nature. If then it is contrary to nature, it will not have any logos (rationale) in nature, just as artless cosntruction has no logos (rationale) in art.”[2] This resonates with my experience of evil; it is senseless and awful, and destructive precisely for that reason. This does not “get God off the hook,” beyond saying that He is not the creator of evil, but it does explain why theodicies ought to be avoided. For, in the end, they become cruel attempts to gloss over the existential reality of people’s suffering with abstract syllogisms that cannot speak to the core of their suffering.[3]

Silence on theodicy does not, however, mean failing to address suffering. For Scripture does give an answer to the problem of suffering, but it is never abstractly philosophical, it is always about what God is doing.[4] The people of Israel cry out as slaves and God sends Moses to rescue them, the land and the poor cry out under the oppressive regime in Jerusalem and God exiles the people to Babylon, and, finally, the world cries out under the weight of incoherent evil and God Himself comes among us, suffers, dies, and is raised again as a sign of new life, promising that he will come again, and that when he does “he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away” (Revelation 21: 4). And, in the meantime, we are called to act alongside to ourselves alleviate pain and suffering and spread the good news of the coming of God.

Kevin G.

Latest posts by Kevin G. (see all)

- All the Company of Heaven: Praying to the Saints - October 31, 2016

- C.S. Lewis, Roman Catholicism, and Bad Apologetics - August 1, 2016

- Sabbath and the End of Work - May 24, 2016