The Doctrine of Theosis: a Case for Divine Melancholy

For either He will change me and make me imperishable, or the Imperishable will be changed to corruption. And thus it is possible that I would not know that He has suffered and become like me. But if I have become wholly imperishable and united to the Imperishable from my perishable condition, then how would I not perceive it with my senses, how would I not see by experience itself, nor know that I have changed to what I was not?-St. Symeon the New Theologian, Divine Eros, 267

The doctrine of theosis is not something that you hear about in Sunday sermons, perhaps because it seems to counter to what we have been taught to think of sin. Theosis, or divinization/deification, is the Christian doctrine that states by being baptized into Christ’s death, we literally are transformed into the being of Christ—essentially, we become divinized, we taste the nature of God and become gods. As Augustine put it in a sermon, “If we have been made sons of God, we have also been made gods.” Or, as Bernard of Clairvaux claimed:

[R]eal happiness will come, not in gratifying our desires or in gaining transient pleasures, but in accomplishing God’s will for us… O sweet and gracious affection! O pure and cleansed purpose, thoroughly washed and purged from any admixture of selfishness, and sweetened by contact with the divine will! To reach this state is to become deified. As a drop of water poured into wine loses itself, and takes the color and savor of wine; or as a bar of iron, heated red-hot, becomes like fire itself, forgetting its own nature; or as the air, radiant with sun-beams, seems not so much to be illuminated as to be light itself; so in the saints all human affections melt away by some unspeakable transmutation into the will of God. For how could God be all in all, if anything merely human remained in man? The substance will endure, but in another beauty, a higher power, a greater glory. (On Loving God, Chapter X)

More recently, C.S. Lewis, in his book Mere Christianity, wrote:

If we let Him—for we can prevent Him, if we choose—He will make the feeblest and filthiest of us into a god or goddess, dazzling, radiant, immortal creature, pulsating all through with such energy and joy and wisdom and love as we cannot now imagine, a bright stainless mirror which reflects back to God perfectly (though, of course, on a smaller scale) His own boundless power and delight and goodness. The process will be long and in parts very painful; but that is what we are in for. Nothing less. He meant what He said.

What are we, as modern Christians, supposed to do with this strange doctrine? Can we really believe it? To do so it would take a radical transformation of our contemporary view of sin.

At the heart of theosis is a very real understanding of, and belief in, sin. Sin is not a cultural taboo; it is a very real thing that draws us away from our assent to the will of God (theosis). What troubles me most about equating sin to social prohibition is it immediately sets up a dichotomy of me the sinner vs. you the righteous one. The proponents of this idea of sin as a cultural construction are quite clever in pointing out this power struggle. Yet, in the Christian tradition, sin is a separation of me from God, which leads to a differentiation of me from you. Sin for a Christian, to put it philosophically, is transformation of the self into a being-towards-nothingness; it is not an action that stems from the social consciousness, but a rejection of what we as Christians claim as a core tenet: our very being is found in our relationship with God.

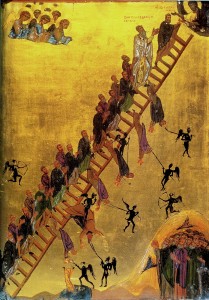

When we sin, we deny the way of being-in-the-world that Christ exemplified on the cross; our sin is our refusal to let our will be conformed, through obedience, to the desires of God. Personally, what I find missing in my daily Christian practice is a real sense of mourning over my sins. Repentance and forgiveness have become second nature to me, so much so that my sin, in a very real way, doesn’t matter any more. This, perhaps, is a repercussion of sentimental Christianity. Yet, when I dig into Christian history, what I come up against time and time again in these writings is an experience of real despair over sins: in other words a divine melancholy. Divine melancholy is a recognition of, and sorrow over, one’s sinful state. It is recognizing, and embracing, an impoverishment before God. Melancholy brings me to a place where I can renounce my sinfulness, where I can give up my desires that lead me away from discovering my true self—for, only when I am truly sorry for something will I resist it the next time temptation arises; it is only when I cast off the world/sin, I can ascend the ladder of virtue that leads me to God.

Divine melancholy is discovered in the refinement of virtue through an understanding of our sins in light of God’s righteousness. This acceptance, according to II Peter, leads to knowledge, self-control, steadfastness, godliness, brotherly affection, and love, all things that help us to participate in theosis. (II Peter 1:4-8) When we don’t cultivate a sense of melancholy over our sins, we train, according to II Peter, our hearts in πλεονεξια—greed that seeks advantage over another, and we become slaves of φθορας, mortality. Essentially, when we deny that our being is found in Christ we become like the animals who follow their own instinct–we do not seek to become like God, we do not accept salvation, but, instead, we make a mockery of the cross. (2:3, 3:19) But, when we proclaim Christ, when our lives are full of virtue that is brought about through a life of divine melancholy, we are transformed from glory to glory. Because we are being changed into the image of Christ, we become transfigured (μεταμορφουμεθα) and reveal the splendor of the cross. (2 Cor. 3:18)

Therefore, being changed, we are no longer beings-towards-nothingness, but beings of the immutable and everlasting God, who, as Irenaeus reminds us “[out] of his boundless love, became what we are that he might make us what he himself is.” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies, V) Let us then embrace melancholy so that we may become what Christ is! Fair warning, theosis changes our vision of the world; it opens up our eyes to suffering, and give us a desire to suffer for the world. But, that isn’t true suffering. To quote Leon Bloy, “The only real sadness, the only real failure, the only great tragedy in life, is not to become a saint.” There is great joy to be found in melancholy; oh, let us go and seek it now!

A.A. Grudem

Latest posts by A.A. Grudem (see all)

- How to be Thankful - September 12, 2016

- The Feast of Thanksgiving - August 12, 2016

- The Nicene Creed: “And [we believe] in the Holy Ghost…” - July 7, 2016