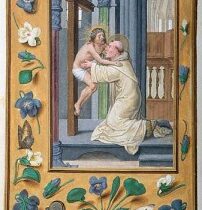

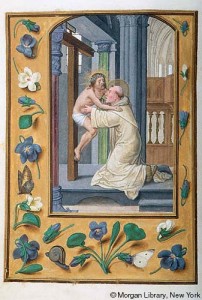

What Happens When We Invite Christ Into Our Hearts?

“Man’s virtue is that by which he seeks eagerly for his Creator, and when he finds him, holds to him with all his might.”- Bernard of Clairvaux: On Loving God

“Man’s virtue is that by which he seeks eagerly for his Creator, and when he finds him, holds to him with all his might.”- Bernard of Clairvaux: On Loving God

“Be complete as your heavenly father is complete.” –Matthew 5:48

Most of us have been to a church where the pastor gives an altar call. It usually happens at the end of a sermon when those in the congregation, who have not accepted Christ as their personal Lord and Saviour, are asked to repeat a rote prayer that asks God to come into their hearts and save them from their sin. But what exactly are we asking God to do when we repeat these words? Is it just for non-Christians? What does it mean to ask Jesus into one’s heart? Is it just a plea to be moral and not sin anymore, or does it have some deeper meaning, a meaning that we have lost in rigmarole of modern Christianity?[1]

What if I were to tell you that the classic Christian understanding is morality and virtue are different things, and while being moral isn’t a bad thing, attaining virtue is something far greater? Would you accuse me of parsing terms? Certainly morality and virtuous living go hand in hand, but I will argue that virtue differs from morality in as much as virtue is the final end, the telos, of a Christian’s life, whereas morality is an incomplete means to that end.

While one may commit a moral act it may not be a virtuous act, whereas a virtuous act may not immediately be seen as a moral act, a choice between right and wrong. While morality has to do with correct choices, often determined by societal impulses, Christian virtue has to do with living a life that is grounded in the presence of God. Therefore, when we follow the pastor and invite Christ into our hearts what we are really doing is asking Christ to complete our actions and to make them virtuous by his participation in them. Thus, when Christ commands his listeners to be perfect as their heavenly Father is perfect, he is not saying that they should be morally just (though this isn’t a bad thing), he is stating that they should be complete in their actions (the Greek word that Matthew uses is teleios, which means fully developed/complete) just as God in heaven is complete in the fullness of his glory. The main ramification of Christ’s claim is that all moral actions are worthless without the fulfillment of God’s presence. Viewed in this way, Christ was not a moral teacher, instead he taught virtue, and it is through his virtue that he calls us to be completed by participating in the life he has prepared for us. This is not to say that Christ’s actions were not moral, but they overcame cultural morality by the fact that they were virtuous—Christ’s actions, including his death on the cross, were complete/virtuous because of his union with the Father and not because of the rightness of the act in itself.

What this means is that whenever we act we have the opportunity to be virtuous. This goes beyond moral action; it strikes at the very heart of who we are as human beings. The very fact that you are an accountant, or a barista, or a garbage collector means that you have the possibility of participating in the virtue of God. In fact, going to a baseball game, writing a paper, having sex, or eating a meal can be virtuous as well—all these things can be a means of God bringing about completeness in our lives. Virtue, as seen in the Bernard quote above, is the means that we use to seek God, and the means through which God completes us, the means through which God makes us more like himself. Therefore, all our actions have the possibility of virtue; all our experiences can draw us up into the presence of God—this is the holiness of the everyday; this is the magnificence of Christian practice.

While this may sound fine and dandy, what exactly does this look like in practice? How exactly do we acquire virtue? Well, the first step sounds remarkably similar to that prayer that the pastor asks the congregation to participate in. That prayer—as silly as it may sometimes seems to us who have heard it over and over again—is the foundation of a virtuous life. By asking Christ to come into our hearts, by appealing for salvation, we are seeking his participation in our quotidian experiences. It is something, according to John Climacus, that many of the desert fathers did daily, and it isn’t a bad thing for us to do every morning either. This has nothing to do with the assurance of our salvation; instead it is an acknowledgement of the way the joy of our salvation interacts with our jobs, habits, and pleasures. In this way virtue has less to do with our moral choices—e.g. Cheetos vs. kale chips (I have it on good word that God prefers Cheetos)—and more to do with the way God interacts or withdraws his presence from these choices. In the end virtue has less to do with golden means, categorical imperatives, and moral absolutes, and more to do with invitation, spiritual practice, and humility. For, while it is the presence of God that makes us holy, not our actions, it is our actions grounded in the holiness of God that give rise to virtue, to God’s presence in our lives. It is my hope that this humble seeking after virtue may make our use of moral injunctions as a determinate of holiness fade away in the actuality of God’s presence. Let us remember everyday to ask Christ into our hearts so that we may be purified by the refining fire of his virtue.

[1] This post, in many ways, is an answer to Justin’s previous post Does God Watch While You Have Sex. At the end Justin asks the question, “What would it mean for our practices of eating and sex if we recognized that God was watching and participating?” I answer Justin by saying that it would not mean much if God was just watching (fear of God’s wrath may lead to right action for a brief period of time). But, as I will argue below, when we invite God to come into our hearts we are asking God to participate in our lives, we are asking God to help us, to complete us; it means that we are developing virtue.

A.A. Grudem

Latest posts by A.A. Grudem (see all)

- How to be Thankful - September 12, 2016

- The Feast of Thanksgiving - August 12, 2016

- The Nicene Creed: “And [we believe] in the Holy Ghost…” - July 7, 2016