The Practical Value of Sabbath

One of the better habits my time in Vancouver instilled in me was the practice of Sabbath-keeping. I had to be slowly weaned off the 24/7 work-week and introduced to a full 24-hour time span that was not focused on all the doings that occupied the other 144 hours of the week. The value I place on Sabbath is not rooted in some legalistic ritual. Instead, it is grounded in practice by example, which was first evidenced to me by a certain sage professor and his wife. He pointed my peers and me to a theologian that he believed in many ways captured the spirit of Sabbath through his writing, the German theologian Jürgen Moltmann:

Though, formally speaking, the Sabbath belongs to the cycle of human time, its nature allows it to break through the cyclical rebirth of natural time by prefiguring the messianic time. The Sabbath is part of the cycle of the week, and yet, by virtue of the promise which, in the mode of anticipation, it already fulfils, it is the sign of the coming freedom from time’s cyclical course. The sabbath stands in time, but it is more than time, for it both veils and discloses an eternal surplus of meaning.[1]

Sabbath, residing in the here and now, shakes us from the ordinary. It shifts the focus from the quotidian sounds, motions, routines and concerns that occupy the vast majority of our time and allows space to not only rest, but to reveal a hope that is often crowded out. It, in a sense, is much like the practice in a yoga where you are told not to ignore the thoughts that come trampling into your mind as you move through sun-salutations, but instead to recognize the thought and then simply let it go. The practice of Sabbath is not about ignoring the concerns of day-to-day life, but rather reorienting them in light of that to which Sabbath time discloses. For those of us with obsessive qualities it forces us to not be permitted to be “productive” at all times with our many projects. It brings us into a space without our mundane idols. It forces us to not take ourselves and our time so seriously.

Sabbath brings rest. This may possibly mean a nap. But, in my experience it has often meant something different. Rest signifies a HALT. A day without alarm clocks, iCalendar, or to-do lists. A day that does not allow me to be one of my many convenient distracting labels (e.g. teaching assistant, student, “high-functioning” adult), but rather to be Rachel: daughter of the Creator God; co-heir with Christ; delighter in creation.

And we desperately need this kind of rest because:

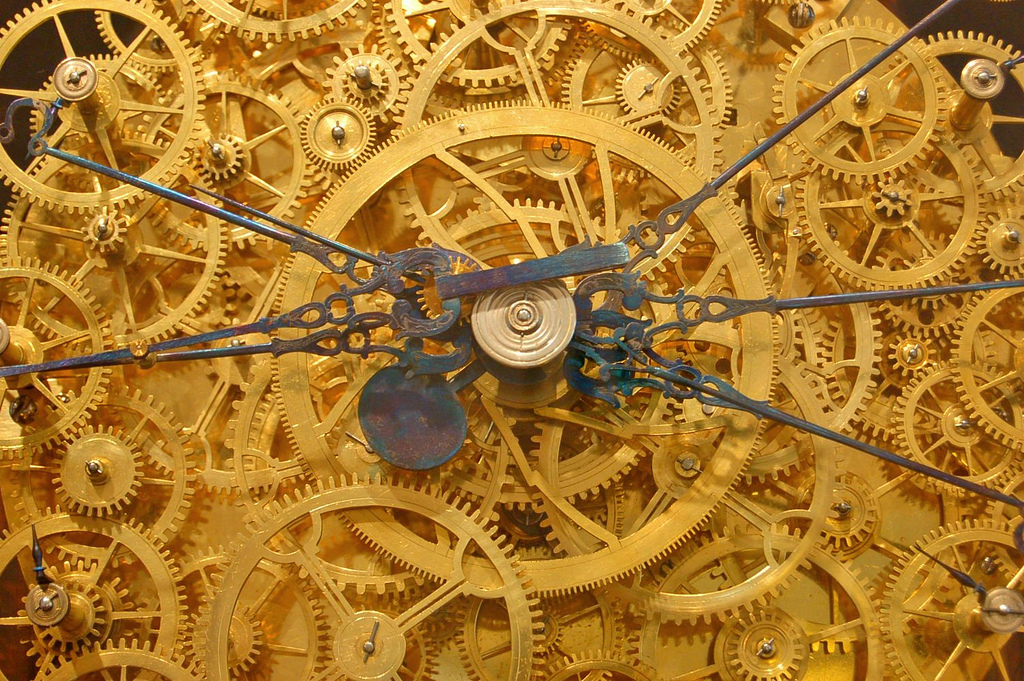

[t]he clock reduces living time – time as we experience it – to mechanical time. The clock became the key machine of the modern industrial age. As a result, human beings have become alienated from the rhythms and cycles of their bodies. And this is especially true of the woman. The body is turned into an instrument for labour and for enjoyment. People are only conscious of it when it stops performing its proper service and falls ill. As a medium for the instinctive, emotion impulses of the whole person, it is becoming unknown. Receptivity, spontaneity, and wholeness of being are lost to the person who is increasingly turned into the subject and object of his own self.[2]

There is no doubt that I am inclined to be a mechanized creature. There is also sufficient evidence that often I don’t recognize my own self-abuse and/or improper use until I physically or emotionally crumble. Sabbath offers a preventative measure. It forces me to un-mechanize. Part of the value I have recognized in Sabbath rest is that often it is not so restful, but actually a bit jolting: it reacquaints me with this self that I have treated like a machine throughout the week. Often what I am presented with is a wilted, tired, anxious, stressed, joyless robot of a creature.

Sabbath serves both as a time for me to tip my hat to and take a walk with my Creator, as well as introduce myself once more to myself. It offers readjustment and reorientation. It permits space to repent of my neglect of myself, creation and God. It gives time to learn to make bread. It helps me to remember to play.

And, as my sage professor would insist, it is also a time to bring sexy back.

[1] Moltmann, God in Creation, 286.

[2] Moltmann, 49.

photo credit: Curious Expeditions via photopincc

Rachel

Latest posts by Rachel (see all)

- On Fairy Stories - October 20, 2016

- Are Women Human? - August 15, 2016

- The Nicene Creed: “…who spoke by the prophets.” - July 11, 2016