The Nicene Creed: “…to judge the quick and the dead…”

**This post is part of a series reflecting on the Nicene Creed**

| << Previous post | View series | Next post >> |

From thence he shall come again, with glory, to judge the quick and the dead; whose kingdom shall have no end.

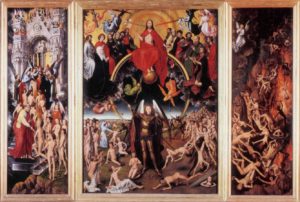

The Creed has it all. The key topics of systematic theology, whether written by the deeply conservative or the modern German liberal, are all found in the creed. Theology proper—the study of God, as Rachel wrote about. Christology—the study of Christ—and soteriology— “for us and for our salvation.” Thursday’s blog post will feature the first post on pneumatology, the doctrine of the Holy Spirit, and today is our first taste of eschatology: the study of death, judgment, and our final destiny. The notion of a final judgment has captured the imagination of Christians for many centuries. Countless paintings and altarpieces are devoted to the topic; today’s chosen image is one such altarpiece created in the 15th century by Hans Memling. That the end times remain of interest can be seen in the fact that the bestselling Evangelical books in North America are the “Left Behind” series. In today’s passage, we are invited to think about what is to come, about the future. Christianity, though rooted in the historical coming of Jesus, looks forward to the future, to a time of judgment and the never-ending reign of Jesus.

from thence he shall come again, with glory, to judge the quick and the dead; whose kingdom shall have no end.

These 21 words of this creedal sentence bring to mind two biblical passages in particular: Matthew 25: 31-46 and Revelation 20: 11-15. The passage in Revelation features the judgment from the great white throne: “And I saw the dead, great and small, standing before the throne, and books were opened. Then another book was opened, which is the book of life. And the dead were judged by what was written in the books, according to what they had done.” The passage in Matthew not only speaks of this final judgment, but links the Kingdom of God with eternal life:[1]

“When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, he will sit on his glorious throne. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate the people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. He will put the sheep on his right and the goats on his left. Then the King will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world. […] Then he will say to those on his left, ‘Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels. […] Then they will go away to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life.”

This future kingdom is, I believe, the same kingdom as the Kingdom of Heaven/God mentioned 50 times in the gospel of Matthew alone. The kingdom is a key element of Jesus’s earthly ministry. As my commentary explains, “The kingdom of heaven/God in the preaching of Jesus as recounted in the Gospels is the reign of God that he brings about through Jesus Christ—i.e., the establishment of God’s rule in the hearts and lives of his people… the creation of a new order of righteousness and peace.” According to N.T. Wright, “the main theme of Jesus’s public career was God’s kingdom.”[2]

In the 19th century, largely due to the influence of the Enlightenment, theological focus was given almost exclusively to the kingdom of God in its immediate meaning. It was a private and moral thing, a supreme ethical ideal. This should not surprise us, nor is it entirely incorrect. In Matthew 25, the judgment of Jesus is on the criterion of what was done for “the least of these.” Similarly, the passage in Revelation states that the dead were judged “according to what they had done.” For these 19th century theologians, then, the kingdom of God was explained in moral terms, not spatiotemporal terms. In the early 20th century, Albert Schweitzer and Johannes Weiss critiqued this moral interpretation and “rediscovered” the eschatology of Jesus. Their views and subsequent critique of their views are interesting (and you can read much on the topic) but in this short space, I will simply note that it seems to me that to ignore the spatiotemporal element of Jesus’s kingdom is to ignore the rest of these passages on the judgment and kingdom as they speak not only of what we have done “for the least of these” but also of everlasting life and our participation in the eternal reign of Christ. As Stephen Webb explains, “In the resurrection, God conquers death, but in the ascension, Jesus Christ transforms the cosmos. Everything about the nature of that cosmic transformation depends upon the question of space. By ‘real place’ I mean a reality that is in some kind of continuity with the space-time of our world.” Webb goes on to note the continuity and discontinuity between earth and the realities of Heaven.

“If it is simply continuous, then we will not need to be transformed to enter into God’s presence. If it is utterly discontinuous, then God’s kingdom will end up replacing, rather than transforming, our world. How we think about the afterlife depends upon how we balance the continuities and discontinuities between heaven and earth.”[3]

How we think of these continuities and discontinuities differs, I am sure, from the original authors of the creed. These 21 words tell us very little about this future judgment and kingdom. These words don’t tell us if we are right to hold a notion of “inaugurated eschatology,” meaning the kingdom of God is already near and yet still waits for future fulfillment. They don’t tell us how to balance the notion of the resurrection as the inauguration of this new kingdom with Jesus’s words that the kingdom of God was “prepared since the creation of the world” and with Jesus’s declaration that the kingdom of God “is at hand.” They don’t help us figure out what it means to be saved by grace alone but judged “by what we have done.”

Perhaps this is what makes the creed capable of surviving throughout the centuries. It seems to me that the coming of the kingdom remains as much a mystery to us as it did to the original authors of the creed. We are both holding to a hope spoken of in the Scriptures and it is for each generation to discover these words anew, bolstered by the teachings of the previous generations. This last line of the the paragraph devoted to “the Son” demonstrates the ongoing nature of the faith, of the kingdom. Christianity, while rooted in historical events, looks forward to more historical events—to the resurrection and the never-ending kingdom of God. These 21 words allow for a variety of questions and answers. There is space for the difference of historical circumstance while still declaring a future and universal hope.

[1] Cf. also Matthew 19:28-30 and 16:26-28; It is interesting to note that the addition of the line “whose kingdom shall have no end” is added only when the paragraph on the Holy Spirit is added. The never-ending kingdom is added to the creed at the same time as the line about the “life of the world to come.”

[2] N. T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God, 406

[3] http://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2013/12/the-problem-of-place-in-douglas-farrows-ascension-theology

| << Previous post | View series | |

| << Previous post | View series |

Robyn

Latest posts by Robyn (see all)

- I’m A Man But I Can Change? Human Nature and Human Enhancement - December 12, 2016

- The Nicene Creed: “…to judge the quick and the dead…” - July 4, 2016

- Can Hermeneutics be Ethical? Ricoeur and the War - June 7, 2016