The Nicene Creed: “…Crucified for us…”

**This post is part of a series reflecting on the Nicene Creed**

| << Previous post | View series | Next post >> |

And was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate; he suffered and was buried.

To follow Ryan’s line of questioning from his post in the series, can we actually make relevant the substance of the Nicene Creed in the life of the modern Christian? Ryan cites Wolfhart Pannenberg on the essential criteria for navigating whether contemporary Christians might appropriate a creed. First, Pannenberg asserts that understanding the historical context and original intent of the creed is essential and that we must judge those theological claims with contemporary biblical scholarship. Given those two things, Pannenberg wonders if the creed can be meaningful to the Christian with the “problems and convictions of the present understanding of reality.”[1]

And so, the question is set: Can Christ’s crucifixion and suffering under Pontius Pilate be imported into the lives of contemporary Christians? Into their current “problems and convictions of the present understanding of reality?” Can the theological implications of Christ suffering and crucifixion have value to the modern mind?

It is hard for me to imagine that most Christians are thinking about vast theological implications of the texts when they recite the Nicene Creed. In the section I am dealing with today, I do not think I have ever considered the various theories of atonement in midst of reciting the small sentence on Christ’s crucifixion and suffering under Pilot. I admit that most of us are not actively thinking of the thought-world of those who scribed the original creed.

To deal with actual text for a moment:

Atonement theories were not the topic discussed at Nicaea. Yet, how we interpret Christ’s divinity directly affects our understanding of the cross. While the crucifixion is given few words in the Nicene Creed, it is the chief cornerstone of the incarnation’s identity. One can imagine how different views of the divinity of Christ might change the function of the crucifixion. The Arian rejection of Christ’s divinity would imply that his work on the cross would be ineffective; it is the Son’s being consubstantial with the Father that makes the crucifixion such a distinctive moment in history. Anything less than God dying on the cross makes the crucifixion nothing more than a tragedy.

Athansius saw the Arian heresy as asking the wrong question, which happened to be the same ones Christ’s opponents and mockers asked. “Why do you, a human being, make yourself to be God?” For Athanasius, the proper question would be: “why did you, being God, become a human being?”[2] It is precisely the issue of Christ’s suffering on the cross as God that is the issue for Athanasius. What is so important to understand for Athanasius and other patristic theologians is that God does not cease to be God when entering into human suffering.[3] It is, in fact, the particularity of Jesus as the God-man that allows him to suffer in the way he does. Jesus’ life is directed toward the cross and toward the suffering he endured on our behalf.

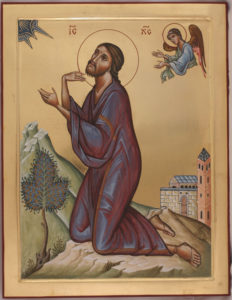

The scene of the crucifixion is set by the last supper and the experience in the Garden of Gethsemane. In the garden Christ asks his Father to pass the cup he must drink—a cup that represents the eschatological wrath of God. Christ’s “yes” to the wrath is consistent with his eternal relationship to the Father; but incarnate, it reverberates through the whole of human existence. Christ’s “yes” is spoken louder than humanity’s “no.”

From his suffering prayer and his being surrendered over to the soldiers, Jesus fully accepts his fate of suffering—not just the cross, but the beating he will take well before he sees the nail and hammer. The crucifixion is above all else, “the full achievement of the divine judgement on ‘sin’ summed up, dragged into the daylight and suffered through in the Son. Moreover, the sending of the son in ‘sinful flesh’ took place only so as to make it possible to ‘condemn sin in the flesh.’”[4] Thus, Christ as both fully human and fully divine is the mechanism that allows God to simultaneously be the object and subject of the wrath upon sin. Recognizing Christ as the “way, the truth, and the life” means to accept that divine act of the cross.

Christians today live in the wake of the full movement of the incarnation’s life, crucifixion, and resurrection. There is no other foundation from which to make sense of the Christian narrative. And this bring us back to our original question: Can Christ’s crucifixion and suffering under Pontius Pilate be imported into the lives of contemporary Christians?

Yes.

Will most Christian understand the complex history of council of Nicaea? Will they have an intellectual grasp of the important thinkers that clarified the central tenants of the faith through the creed they recite? The point is not that Christians immerse themselves in the thought-world of the 4th century theologians, but rather, immerse themselves in what those theologians were protecting: a coherent salvation narrative that deals with personal suffering, sin, and participation in God’s salvific plan. If one cannot sensibly deal with the motifs of sin, salvation, wrath, and atonement, then we are talking about a conflict of paradigms and worldviews, not a usurpation of truth by “present understandings of reality.”

__________

[1] Wolfhart Pannenberg, The Apostles’ Creed in the Light of Today Questions, vii.

[2] Athanasius, On the Council of Nicaea, I.

[3] Paul Gavrilyuk, “God’s Impassible Suffering in the Flesh,” in Divine Impassability and the Mystery of Human Suffering. 143.

[4] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Mysterium Paschale, 119.

Latest posts by Lance (see all)

- The Nicene Creed: “one baptism for the remission of sins.” - July 19, 2016

- The Nicene Creed:”…on the third day he rose again…” - June 30, 2016

- The Nicene Creed: “…Crucified for us…” - June 27, 2016