Lenten Love

Lent: forty days of fasting. Jesus’s forty days in the wilderness, Noah’s forty days of rain, Moses’s forty days on Sinai, Elijah’s forty day walk to Horeb, Goliath’s forty days of challenge before the nation of Israel: all of them are forty days of trial building up to an encounter with God’s grace. Yet, the greatest of these is Lent. Lent is the annual enactment of the cost of the love that lies at the foundation of all creation.

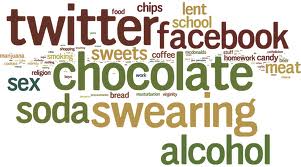

These are some big claims. In a world where Lent is often no more than the “giving up” of chocolate, coffee, beer, meat, or the internet, it hardly seems fair to compare it to the forty days of rain that annihilated the entire population of the Earth or with Elijah’s forty days without food or water as he hiked through the desert. But, where Elijah ends his forty days with the still small voice, and Goliath’s forty days end with his being slain, and Jesus’s forty days end with his defeat of temptation, our forty days ends with the death and resurrection of God himself bringing the whole of creation back into communion with himself. This is the central moment of God’s love.

Fasting is critical to this love because, as Barney pointed out a few weeks back, belief is more than an intellectual or rational assent, it is a practice. Christian practice promises to bring us into the divine love: the love in which all love finds its origin and at the heart of which lies the divine fast, the divine self-giving. As Pope Benedict XVI wrote in his first encyclical:

This is love in its most radical form. By contemplating the pierced side of Christ, we can understand the starting-point of this Encyclical Letter: “God is love” (1 Jn 4:8). It is there that this truth can be contemplated. It is from there that our definition of love must begin. In this contemplation the Christian discovers the path along which his life and love must move.[1]

1 John also roots our understanding of love in the self-giving act of Christ: “This is how we know what love is: Jesus Christ laid down his life for us. And we ought to lay down our lives for our brothers and sisters” (1 Jn 3:16). We must be careful not to confuse this love with the “love” propounded in country music, romantic comedies, and self-help books where “love” is the source of self-fulfillment. Rather, this is the “love” of he who loves his life and will lose it. The Bible does not present love as a peaceful easy feeling. Instead, love is shown to be a painful and costly endeavor.

Lent participates in and embodies that eternal self-giving love of God and serves as the central time of love in the Christian calendar. Lent brings into the liturgical practice of the Church the truth that:

The coming lordship of God takes shape here in the suffering of the Christians, who because of their hope cannot be conformed to the world, but are drawn by the mission and love of Christ into discipleship and conformity to his sufferings. This way of taking into consideration the cross and resurrection of Christ does not mean that the “kingdom of God” is spiritualized and made into a thing of the beyond, but it becomes this-worldly and becomes the antithesis and contradiction of a godless and god-forsaken world.[2]

Here, Moltmann brings the suffering of Christ, through the suffering of Christians, to its fulfillment in the kingdom of God and a world in communion with the Lord. This fundamental hope of the Gospel is what makes the cost of love worthwhile. The promise of Easter is so much more than the simple freedom to not sin. At the conclusion of Lent, suffering ends with the radical communion of the whole cosmos with the risen Christ.

Thus we have a circle we must struggle not to break. God loved us to the point of self-sacrifice on the cross so that we may love to the point of self-giving to participate in the fulfillment of the kingdom of God and the reconciliation of divinity and creation.

It is quite easy to divide this formulation. We all know individuals who emphasize the suffering of Christ and the work of God so heavily that being Christian appears to contain no suffering at all, but holds only promises of prosperity and blessing. We also know individuals who so emphasize the need for us to bring in the kingdom of God that they reduce the work of Christ to social justice or those who so focus on the second coming that they become blind to the world right in front of them. And, most dangerous of all, we know individuals who are so focused on self-giving that they burn themselves out, are unwilling to take care of themselves and their families, and become impotent in the face of the call to love. These are all in one way or another a product of pride and warped self-love.

Love is hard. To love as God loves without warping it to our own desires requires practice. Hence, the significance of Lent is to return year after year to an embodied practice that reminds us of the true gift of love, the cost of love, and the fulfillment of love.

[1] Pope Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est, 1:12.

[2] See Jurgen Moltmann, Theology of Hope, Chapter 3.

J.W. Pritchett

Latest posts by J.W. Pritchett (see all)

- Is the Internet Making us Ungodly? - April 21, 2014

- Does God Watch While You Have Sex? - March 17, 2014

- Lenten Love - March 3, 2014