Why do we trust the Bible?

Rachel recently wrote a great post on how we give authority to the Bible. Here I want to examine some of the issues around why we do so.

Traditionally, Evangelicals have made the Bible the basis of all their theological beliefs. The final call, the ultimate standard for whether to believe something is whether “the Bible says so.” Even when something seems nonsensical, absurd, or just enormously unlikely — if the Bible says it, we are committed to believing it. This enormous weight of authority placed on the text of Scripture can only be forgotten in a context in which everyone takes it for granted. But if we regularly encounter people who do not share this attitude, we cannot ignore or avoid the question: why do we trust what the Bible says?

Nobody is born “believing the Bible.” Something or someone has led us to this belief, which begins by its appeal to something innate to who we are. Was I swept away by the transforming power of the Holy Spirit in my life? Was I convinced by a compelling and reasonable argument? Was I embedded in a warm community of wise and loving role models? Whether it was reason, experience, community, or whatever it was – that ‘something’ is a higher authority to me than the Bible, because it is the reason I began to trust the Bible in the first place.

I think this is important for two reasons. First, whatever reason we came to trust the Bible continues to influence our way of interpreting it. Whatever ‘prior commitments’ (to reason, experience, etc.) which led us to Scripture will keep operating as we read it. Second, all of us have beliefs about reality that don’t come from Scripture, and those beliefs will also constantly interact with what Scripture says.

Let me illustrate with an example. One of the more challenging sayings of Jesus is in Matthew 6:

Do not worry, saying, “What will we eat?” or “What will we drink?” or “What will we wear?” For it is the Gentiles who strive for all these things; and indeed your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things. But strive first for the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well.

The face-value implication of this saying conflicts sharply with our experience of Christians throughout history who have died of hunger, thirst or cold, despite seeking God’s kingdom. Perhaps we ourselves can also remember a time when we felt we desperately needed something and our need was not met. The initial moment of disappointment, when what Scripture says (either this passage or another) fails to correspond to the reality we have seen or experienced, produces a conflict. We have a choice: to interpret the Bible differently, or to understand reality differently, or to allow a separation to grow between our understanding of the Bible and of reality. We can read about people and institutions throughout history who made one of these choices when faced with this conflict.

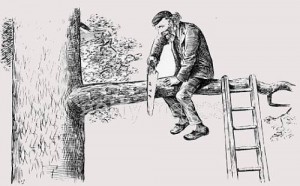

The Bible makes claims about reality. If our understanding of reality and our understanding of the Bible were identical, we wouldn’t need to read the Bible. But where they disagree, there are only three options: our understanding of Scripture is wrong, our understanding of reality is wrong, or Scripture is wrong. If we, as Evangelicals, rule out the third option, then we need to have solid and robust reasons for doing so which will inevitably govern our approach to the first two options as well. In a sense, our reason for trusting the Bible is like the glue that holds Scripture close to our worldview and forces us to keep reconciling the two. If that glue is weak – if we don’t really know why we give so much authority to Scripture – then we will not bother to reconcile it with reality when there is a conflict. Either Scripture will no longer challenge us, and our beliefs will begin to take shape apart from it, or we will adopt a more fundamentalist attitude, denying the validity of experience and reasoning out (ours or others’) of a fierce commitment to our current understanding of Scripture. The former option leads away from being Evangelical, and the latter leads to self-contradiction and narrowing of horizons, eventually undermining our original reason for trusting Scripture.

I believe that Evangelicals need to spend more time thinking about how and why the Bible is authoritative. It is a scary question, because if we dig up the foundations of our Scriptural beliefs, the process may alter how we understand Scripture itself. We may find that our former reasons were incoherent. Or we may find reasons for trusting Scripture that compel us to be more open to other things we hadn’t previously considered. Part of the adventure of theological and philosophical investigation is that anything could happen! But part of the comfort is that if something really is true, then there will be reasons out there for believing it, even if they rattle our present convictions. May the Holy Spirit guide us as we go on the journey of truth together!

Barney

Latest posts by Barney (see all)

- The Nicene Creed: “One Church” - July 14, 2016

- The Nicene Creed: “…for us and for our salvation…” - June 24, 2016

- Pacifism and Politics: The Tank and the Letter - May 3, 2016